By: Will Riley, a Laurier Institution Blog Contributor

Slowly but surely, an end to the COVID-19 pandemic is visible on the horizon. However, the transition from the “new normal” back to, well, the old normal, is going to be filled with awkward steps. Despite virtual events, the pandemic has primarily led to a great turning inward. Direct contact with others has been sparse, particularly with anyone outside of one’s pre-existing social bubble. As a greater range of social experience becomes available once again, many are going to naturally reassess their priorities. Most important among those: what activities are we able to partake in again that will improve our lives, collectively, so that we don’t just return to the world as it was before, but to something better?

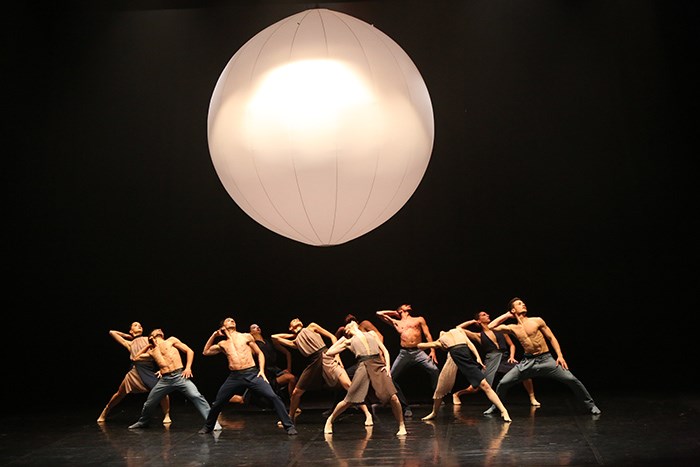

For people who believe a more diverse and inclusive society is a part of that last question’s answer, it’s crucial that cultural festivals, multi-cultural festivals in particular, ramp up in full force once it’s safe to do so. Night markets, food festivals, film festivals, performing arts shows—they are all a critical tool to bring that social life back, more vibrant and varied than it was before.

My own experience working for a multicultural festival demonstrated to me the immense cultural value it can bring to a community, for both attendees and organizers. But it also highlighted the need for a clear aim. Not all methods of promoting diversity are going to operate without contradiction from others. As a vendor coordinator, I managed the non-profit cultural associations and vendors hosting booths at the festival, many which were profit-driven companies selling their wares for an event whose broad goal was “cultural enrichment through supporting local immigrant-run businesses”. Soon enough, conflicts between cultural associations and vendors started to emerge. Most of them were minor, but others demanded contemplation of the very structure and aim of the festival itself. For instance, a private henna artist signed on as a vendor, but so did a Pakistani non-profit to give henna tattoos at no charge. Soon, the private artist was demanding that the festival make the non-profit stop their service so that her own profits wouldn’t be jeopardized. Ultimately, the festival manager concluded that, since this particular festival’s goal was advancing the cause of diversity through the promotion of business, the private artists’ wish should be granted.

I was the one tasked with the unhappy and awkward duty of asking the non-profit to stop giving the free henna. I kept mulling over the episode for a long time; it’s true that since the festival was meant to promote private businesses, ruling in favour of the for-profit artist followed the rules it had set out for itself. But with a different philosophy, one that aimed to promote diversity by simply seeing the greatest amount of cultural exchange possible, things could just as easily have turned out in favour of more attendees getting henna tattoos for free. While I concede that adhering to this second philosophy isn’t always practical in the world we live in, we shouldn’t treat it as if it’s totally off the table.

What I learned while organizing a multicultural festival

While there were many lessons I took from my experience helping to organize multicultural festivals, these are my three main takeaways.

1. Physical celebrations are better than virtual

Nobody can articulate cultural pride more than a member of that culture themselves. Far too many times, rather than exemplifying cultural pride to others directly and viscerally, it must be made to comport with the standards and judgments of media juggernauts to get any visibility in the first place. Oftentimes what is on display is either whitewashed or some kind of caricature.

Festivals leap over this barrier by coming to where people are—physical space—and thereby articulating the way that the organizers think makes the most sense. Festivals forcibly disrupt routines. Not just the routines of people’s daily lives, but people’s mental routines, the things they tell themselves about other people’s cultures so frequently that it can transform into implicit and unrecognized bias, one which is best remedied by direct engagement with that culture.

And my, what routines we have made over the last two years! Experiencing the world through a screen as long as we have created a great flux over relationships with people outside immediate bubbles. The critique of the internet as some cesspool of misogyny, racism, and conspiratorial thinking about any group under the sun is pervasive enough that it can come off as a cliché, but it’s a cliché rooted in something real: one’s image of other people and their culture can become warped if your only experience and knowledge of them is abstract and virtual. For how much the internet has been able to bridge the communications divide between people, remote experiences of the world can breed an intolerant mindset. Sometimes the internet can make people isolated and remote.

And my, what routines we have made over the last two years! Experiencing the world through a screen as long as we have created a great flux over relationships with people outside immediate bubbles. The critique of the internet as some cesspool of misogyny, racism, and conspiratorial thinking about any group under the sun is pervasive enough that it can come off as a cliché, but it’s a cliché rooted in something real: one’s image of other people and their culture can become warped if your only experience and knowledge of them is abstract and virtual. For how much the internet has been able to bridge the communications divide between people, remote experiences of the world can breed an intolerant mindset. Sometimes the internet can make people isolated and remote.

2. Be mindful of sponsorship dynamics

While the cultural response is only a piece of the puzzle when it comes to the advancement of diversity, equity and inclusion, festivals distinguish themselves within by providing something much more tangible. They inhabit an actual material space, and actively demand people’s attention. A festival cannot be as easily ignored as passing around pamphlets; there are people out on the streets having fun, and wanting to join them is a natural response. There is an element of power in establishing and organizing a festival in an actual urban space that is more concrete than it is given credit for, and shouldn’t be treated as negligible. These huge get-togethers facilitate a great deal of social and business connections, both inside and outside their related cultural group. This establishes the festival, and the culture it represents, as a focal point for economic activity and the broader social fabric of the community. The culture is thus moved from the periphery to the centre, a position of power.

This position of power is usually unrecognized. Even festival organizers themselves rarely have the resources to grasp it themselves. This is where the double-edged sword of sponsorship comes into play: huge institutions like banks, national supermarket chains or extractive industries like Alcan are frequent sponsors of large events, in exchange for promotion. Beyond using festivals as avenues for self-advertisement, rhetorically, sponsorship shifts the role of a pillar of the community away from the people that organized the event in the first place, and instead places the credit onto already massive and powerful companies. In this way, the concrete power festivals could generate for their community is instead siphoned off, in a weaker rhetorical form, into the territory of pre-existing hegemons. In organizing the funding of a large cultural event, one which is supposed to bring too-often unheard voices to the fore, one needs to ensure the event won’t accidentally wind up amplifying the voices that are already drowning the others out.

This is not to say that every festival organizer should steadfastly refuse every large sponsor for their event, for risk of recuperating the image of big business. It is simply to say that, if giant corporations think there is some political power in festivals, then the organizers, if they truly believe in advancing policies of diversity, equity and inclusion, should seek to hold on to as much of that for themselves as they can, and have a clear aim for how they will wield it.

3. Show your support where it counts

The best way to promote cultural exchange for its own sake is through the direct support of your local cultural associations and their events. For organizers, this might mean closer vetting of vendors that align with the festival’s goals or message, even if means giving opportunities for organizations with traditionally less visibility or resources to participate. For attendees, individual financial support (when possible) will allow festivals to slowly achieve the independence that could allow them to not be as dependent on the profit motive to maintain themselves. This moment—as the world starts to open up again—is the best time to do so. Hopefully, as we start going out into the world again, and even fuller spectrum of experience is available to everyone.

These Festivals Could Benefit from Your Support and Patronage:

The Vancouver International Bhangra Celebration Society’s 5X Festival

Powell Street Festival Society